A Black Hole in the Distinctiveness Continuum for U.S. Trademark Applications

Marks that border the line that divides descriptive from generic often topple into a virtual “black hole” on the distinctiveness continuum. The owner of such a mark may be required to meet an indefinite threshold of proof to establish with the U.S. Trademark Office that the mark has acquired secondary meaning to consumers as an identifier of source. This article will discuss specific instances in U.S. Trademark practice where this situation may arise and potential approaches to obtaining the applicant’s proposed mark.

Trademark Distinctiveness

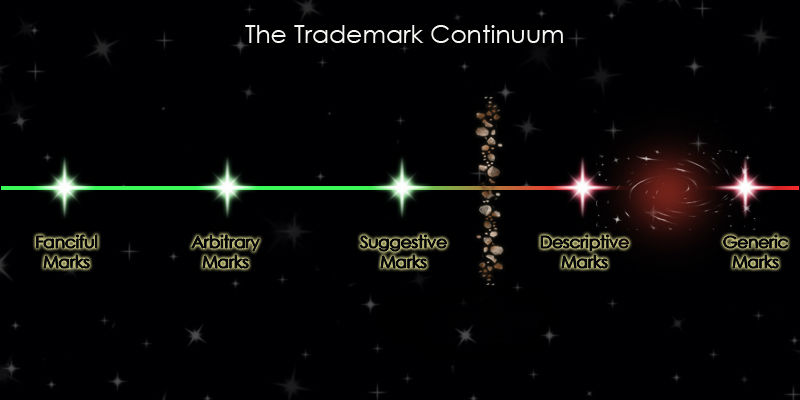

Every trademark falls into one of five major categories along a continuum of distinctiveness, ranging from unprotectable to strong. Arbitrary, fanciful, and suggestive marks are considered strong because they are inherently distinctive, and may be registered on the Principal Register . They are generally more readily enforced against third parties because they are better distinguished in the minds of consumers. Generic and descriptive marks fall on the weaker end of the scale. Generic terms are not registrable at all and are difficult, if not impossible, to enforce as trademarks in the United States. This is because terms that the general public would view to be generic are easy to confuse in the marketplace when unaccompanied by a distinctive element and, as such, consumers would not recognize them as identifying any one particular source of goods or services and they should not be removed from the realm of free speech. Merely descriptive marks lack inherent distinctiveness, but can acquire distinctive strength from use and investment over time. They may be registered on the Principal Register with sufficient evidence of acquired distinctiveness or on the Supplemental Register, provided they can acquire distinctiveness over time.

Generic and descriptive marks tend to be initially preferred by many businesses because they are straightforward and require less effort and cost in order to educate consumers about the brand. However, proceeding unadvised with these kinds of marks may prove to be costly in the long run, due to a high chance of refusal or of drawn-out proceedings or of difficulties in enforcing the mark against others.

Generic marks are so straightforward that the relevant purchasing public understands the term or phrase primarily as the common or class name for those goods or services. For example, MATTRESS.COM is unregistrable because it is a generic term used in relation to an online retail store in the field of mattresses, beds, and bedding.1

Merely descriptive marks describe an ingredient, quality, characteristic, function, feature, purpose, or use of the specified goods or services. For example, COASTER-CARDS for coasters resembling post cards and suitable for direct mailing has been held to be merely descriptive.2

Highly Descriptive Marks in the U.S. Registration Process

The continuum of different levels of distinctiveness becomes particularly relevant in relation to generic and merely descriptive marks. Somewhere between what is considered generic and merely descriptive is a range of marks that are deemed “highly descriptive” by the USPTO. While a high level of descriptiveness is technically not a basis for refusal, there is a direct correlation between descriptiveness and a mark’s ability to acquire distinctiveness. The more descriptive a mark is considered to be, the more evidence of acquired distinctiveness is required and the more difficult it is to prove that it has become distinctive.

Typically, when an Examining Attorney considers a mark to lack sufficient inherent distinctiveness, she refuses the application on the grounds that the mark is merely descriptive. If she considers that mark to be generic, she also includes an advisory notice to that effect, as a formalized generic refusal is normally not issued at first. If the Examining Attorney deems only part of the mark to be descriptive or generic, she may issue a disclaimer requirement instead.

The applicant may respond with arguments against the descriptiveness refusal or disclaimer requirement, and/or, inter alia: a) a claim that the mark has acquired distinctiveness; or b) an amendment of the application to the Supplemental Register, where permissible.

A claim of acquired distinctiveness requires the applicant’s good faith assertion that, as a result of longstanding use and/or extensive marketing and recognition in the marketplace, the descriptive mark has taken on a secondary meaning in the minds of consumers such that it now identifies the applicant as the source of the goods or services covered to the relevant purchasing public. Commonly, an applicant that has used its mark for five or more consecutive years will claim acquired distinctiveness by way of a simple declaration about the continuous and exclusive use of the mark, and this will be sufficient to overcome a refusal on mere descriptiveness grounds or a disclaimer requirement. An applicant may also claim acquired distinctiveness by other means, such as through the submission of evidence in the form of letters or affidavits of customers, surveys, advertising expenditures, sales figures, and the like. If the Examining Attorney accepts the applicant’s acquired distinctiveness claim, the mark is eligible for registration on the Principal Register.

If the Examining Attorney is not satisfied by the applicant’s submission and considers the mark incapable of becoming distinctive, he may choose to issue a formalized refusal on the grounds of genericness. The Examining Attorney has the burden of establishing genericness by clear evidence that (1) identifies the genus of goods or services at issue; and (2) shows that the relevant public understands the designation primarily to refer to the genus of those goods or services. This test turns upon the primary significance of the term among the relevant public. Because the Examining Attorney has the burden of proof, the applicant is fully informed of the USPTO’s position and can choose to argue against the sufficiency of the Examining Attorney’s refusal.

Alternatively, an Examining Attorney may maintain her descriptiveness refusal without accepting a claim of acquired distinctiveness on the basis that she considers the mark or a portion thereof to be “highly descriptive”. In contrast to a genericness refusal, there is no additional burden of proof on the Examining Attorney to establish that the mark is highly descriptive. Marks deemed highly descriptive require the applicant to meet a higher threshold of proof to establish acquired distinctiveness. The exact amount of evidence in such cases is undefined, as the threshold is discretionary and determined after the fact by the Examining Attorney. The burden is then placed on the applicant, however, since the Examining Attorney need not provide any guidance as to what amount or type of evidence would be acceptable, this burden may prove to be insurmountable.

The Examining Attorney’s discretion in this evaluation creates a virtual black hole in which the applicant has no option to register the highly descriptive mark, except perhaps on the Supplemental Register, if available. Where only a part of an otherwise distinctive mark is highly descriptive, and the applicant wants to acquire distinctiveness in that term, the Supplemental Register ceases to be an option. The applicant can either attempt to win on appeal or, more likely, file a new application for the descriptive component by itself seeking registration on the Supplemental Register either at the outset or as a possible eventuality after examination.

Case Study: Crystal Geyser Alpine Spring Water

During the examination of Crystal Geyser Water Company’s (“Crystal Geyser”) application for “CRYSTAL GEYSER ALPINE SPRING WATER” in relation to bottled spring water, the USPTO required a disclaimer of the allegedly descriptive phrase “ALPINE SPRING WATER”.3 As the mark was ineligible for an amendment to the Supplemental Register because it combined the descriptive elements with the distinctive terms “CRYSTAL GEYSER”, the applicant had the limited options of submitting to the disclaimer, arguing against the disclaimer, claiming acquired distinctiveness, or abandoning the application.

If Crystal Geyser disclaimed “ALPINE SPRING WATER,” they could register on the Principal Register. The disclaimer would create a readily accessible, public, permanent record of the company’s concession that it had no exclusive rights to “ALPINE SPRING WATER” apart from the rest of the mark. However, it should be noted that a disclaimer in a prior registration does not necessarily mandate how the term should be treated in subsequent applications because there are a variety of reasons as to why an applicant may choose to disclaim.

Crystal Geyser attempted to overcome the disclaimer requirement with a claim of acquired distinctiveness. The USPTO did not accept the applicant’s claim, but rather maintained the refusal deeming ALPINE SPRING WATER to be highly descriptive. Crystal Geyser further submitted evidence of its sales of seven billion bottles since 1990 and of successful, multi-million dollar advertising campaigns; however this did not satisfy the heightened, yet unclear requirements set by the Examining Attorney. While Crystal Geyser appealed the Examiner’s decision, the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board upheld the refusal as highly descriptive and deferred to the Examiner’s discretion.

Crystal Geyser simultaneously held a companion application for “ALPINE SPRING WATER” which was similarly refused. The applicant did not attempt to amend that application to the Supplemental Register, however, and instead allowed both applications to be abandoned. It re-applied to the Principal Register for stylized versions of the marks, both of which were ultimately registered on the Principal Register with disclaimers of the phrase “ALPINE SPRING WATER”, as was required in the initial non-stylized filings.

Options for Businesses that Adopt Highly Descriptive Terms in Their Marks

When a business-owner maintains a strong interest in adopting a highly descriptive or generic mark, or one comprised of highly descriptive or generic components, in which he intends to claim exclusive ownership, there are typically two approaches to obtain a registration. First, as initially and ultimately pursued by Crystal Geyser, the applicant can consider the addition of a distinctive element to an otherwise descriptive mark. A distinctive element, if it does not conflict with third party rights, such as a graphic device, font, or color, can strengthen the chances of registration on the Principal Register. However, the descriptive portion of such a mark may be subject to a disclaimer that is permanent and public. Alternatively, the applicant can sometimes pursue registration of the descriptive elements themselves, with an expectation that if a claim of acquired distinctiveness is not accepted, the application can ultimately be amended to the Supplemental Register, where possible.

Depending on the circumstances, either or both options may be advisable. With an understanding of the business’ goals, counsel can advise on the risks of refusal on descriptiveness or genericness grounds or a disclaimer requirement, and help the business avoid the virtual black hole that falls between merely descriptive and generic marks or terms.

The authors wish to thank Danielle Weitzman for her contributions to the research and editing of this article.

- In re 1800Mattress.com IP LLC, 586 F.3d 1359, 92 USPQ2d 1682 (Fed. Cir. 2009)

- In re Bright-Crest, Ltd., 204 USPQ 591 (TTAB 1979)

- In re Crystal Geyser Water Co., 85 USPQ2d 1374 (TTAB 2007)